Search Posts

Recent Posts

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 25.04.24 (100th for Louis Dolce, events, resources) – John A. Cianci April 25, 2024

- Business Beat: Bad Mouth Bikes takes home 3 national awards April 25, 2024

- Rhode Island Weather for April 25, 2024 – John Donnelly April 25, 2024

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern’s Cajun North Atlantic Swordfish, Mango Salsa, Cilantro Citrus Aioli April 25, 2024

- The Light Foundation & RI DEM’s 4th Annual Mentored Youth Turkey Hunt a success April 25, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Dust – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

Copyright © 2022 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Dust comes from different sources. It coats everything we know.

Dust outside is made of fine particles that drift down from the heavens — space dust from meteorites, asteroids, comets, planets, and stars that finds its way into our atmosphere and drifts to earth, pulled in by the earth’s gravitational and electromagnetic field, the particles floating closer and closer to the earth’s surface until they settle on our trees and fields, on the mountains and in the oceans, on our houses, roads, gardens and sidewalks, a fine dust that accumulates over time, a filmy blanket that covers us all equally. Dust outside also comes from fine particles of soil or sand lifted by the wind, often from the Sahara and other deserts in Africa after dust storms, particles that are lifted into the upper atmosphere, picked up by jet streams and are carried around the globe. Outside dust also contains particles from volcanic eruptions and particles created by human beings as we plow the earth or drive our cars and trucks on dirt and gravel roads, as we burn fossil fuels and wood for heat, or stir the earth in other ways, by pit mining or building roads.

Dust in our houses and buildings is twenty to fifty percent dead human skin, which we are always shedding and is always regrowing, combined with human and animal hair and animal dander, when animals live inside as pets, but also from animals that share human spaces – rodents and snakes, mostly — and from the scat and body-parts of the insects that live with us – dust mites, bedbugs, flies and spiders — and the remains of old spiderweb silk. House dust is part plant pollens, part animal fur, part textile and paper fibers. House dust also contains particles created by crumbling paint and masonry and from the ash in wood and coal smoke, particularly in houses with fireplaces, from when the wind blows smoke back down the chimney and smoke floods into the room. The wind brings outside dust – space dust and the dust from the deserts and power plants and volcanos — into houses when doors are opened as we go in and out, and when windows are opened in springtime.

So, house dust is human skin mixed with animal residue, mixed with plant pollens, mixed with the residue of our paper and cloth, mixed with the dust from distant deserts and the dust created by our powerplants, mixed with the residue of the cosmos that has traveled across the light-years and contains evidence of the creation of the universe itself. Dust to dust, the good book says. We are made from dust, live among dust, and return to dust, no one of us taking a different path and all equal before God and history, sitting in our little houses, all encountering the cosmos itself every time we sweep the floor or run a dust cloth over the shelves and banisters, the desks and wardrobes and even over the black plastic of our TVs and computers and the smooth wooden surfaces that make up the furniture in our houses.

Dust to dust. Dust covers all our acts, transgressions, and possessions, conveying a message: you aren’t much and won’t last. Live it up while you can.

–

It was hard to believe how much stuff could be packed into one old house. When Vera Williams opened the door of the old house in Warren, Rhode Island, she thought she was there just to clean and get the first floor ready for her aunt Emma to come home from the hospital. She was there to set the place up so that Emma could go back to living on her own. She thought she’d sweep and dust, wash any dishes that were in the sink, open the windows and air the place out, because Emma had been gone for three months. She thought she’d order up a hospital bed and maybe get some handrails installed in the little first floor bathroom, the one under the stairs that she remembered from visiting there as a child. Maybe take the rugs off the floor, so Emma wouldn’t slip and fall and break another hip, the stroke and one fractured hip being more than enough for an old lady to handle, thank you very much.

Vera wasn’t prepared for the mountains of stuff that was everywhere – boxes and shopping bags filling every room, stacked almost to the ceiling. Old chairs, lampshades, empty aquariums, toys, bags of groceries, boxes of old dishes and silverware, coats and sweaters, and cat beds (without cats, thank God) stacked on top of the boxes which were on and under the tables. The aisle between the boxes were so narrow Vera herself could barely get through to move from one room to the other, and she had no idea how Emma, who was not a small woman, moved from place to place.

Vera was closest of all the cousins. Closest in distance. But closest as a person as well – closest to Emma, closest to Emma’s sisters and brother and sister-in-law — Vera’s mother, Emma’s oldest sister, having passed away twenty years before. The other sisters and her brother, Vera’s aunts and uncle were now in Florida and Arizona. Vera was also closest to her cousins, whom she called a few times a year, just to hold the family together, not that anyone cared much about family anymore, anyone except Vera herself. She was the only one of the cousins who was trained in this kind of thing, just a pediatric PA, true, but the only one who knew about health and health care, so clearly Vera was the one best able to talk to the social workers, nurses and occasional doctor who reached out to family to talk about this elderly woman living alone.

How had this happened? Vera asked herself. How had Emma’s life gone so much off the rails without somebody, without anybody, noticing?

What do you keep and what do you throw out? Emma was of sound mind. Oriented to person, place, time, and situation. She knew who the president was. And she was quite willing and able to give you a detailed opinion about the last one, thank-you very much. As well to comment on how everyone looked, who was sweet on whom among the nurses and doctors, and who was looking hot today.

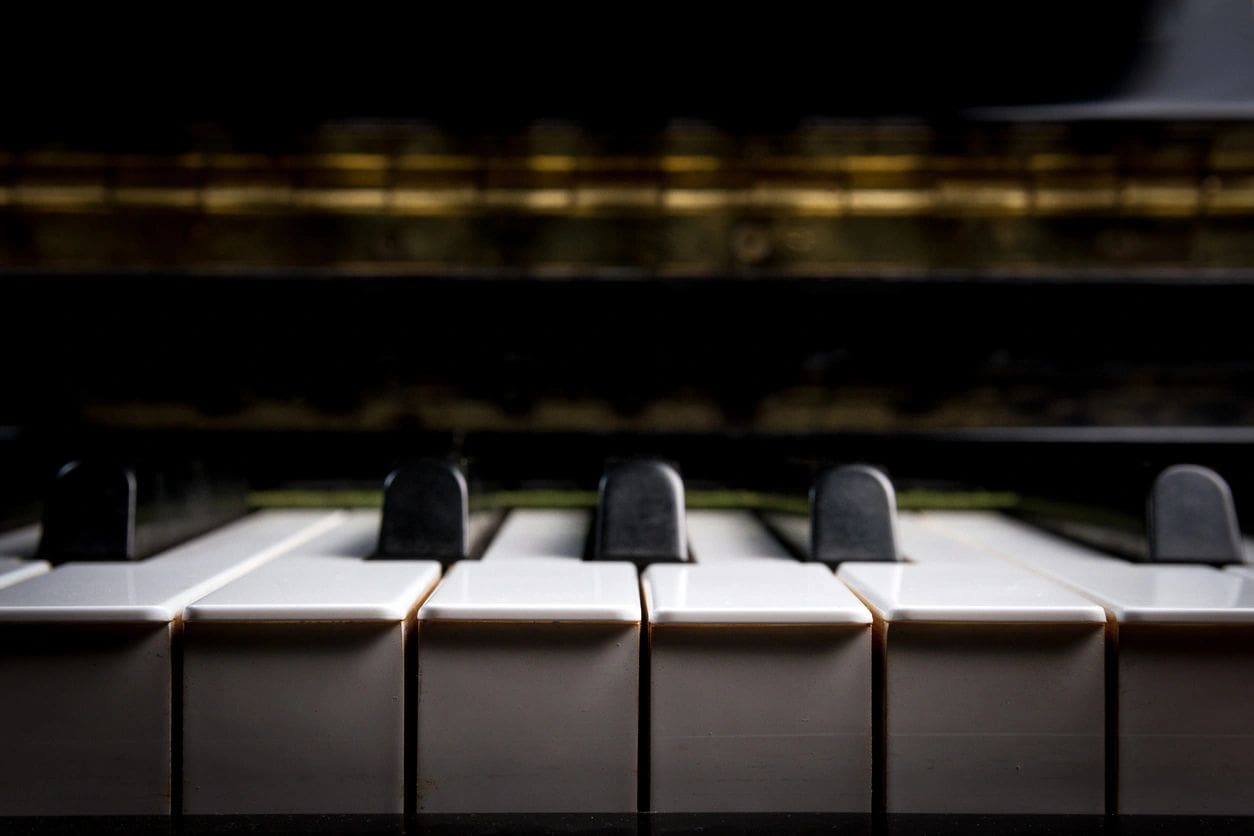

Emma was a hot ticket herself. Or had been. She had lived her life as a free spirit, a piano player who made a living from music, playing jazz in clubs sometimes, teaching piano sometimes, playing in the odd wedding and bar-mitzvah band and even playing for ballet students when she needed a little extra to get by. She had husbands and lovers, but no one ever told Emma what to do.

But when she looked at the mess, Vera wondered if Emma was of sound mind after all. Does someone of sound mind let themselves live like this? Does someone of sound mind collect…. all this…. junk, all these…. treasures?

Emma would be home in two days. Vera got to work.

When Emma Williams played Jellyroll Morton, her fingers almost left her hands. When she played Marian McPartland, she sat straight up and imagined having tea with the Queen. Her fingers were her highway to the stars. When she played, she saw the stars and the planets as if she were floating in the cosmos itself, as if nothing could hold her down.

No one she knew understood this. The others were stuck on the earth, wrapped up with their husbands and wives and their children, with who has playing what sport and where they were applying to college.

None of that was for Emma. There had been a cancer at twenty-four, which meant a hysterectomy. For three years she mourned and only gave piano lessons in her little parlor, in the house where she’d grown up, or played for the ballet school on South Main Street, right before it turned into Hope Street in Bristol, where little Episcopalian and Unitarian and Jewish and Chinese girls from Barrington joined Portuguese, Italian and Irish girls from Bristol and Warren and came to act out their fantasies, in the days of ballerinas and cowboys and Indians.

Emma cried herself to sleep at first. Then one day, walking home from the bus, she saw a globe in a pile of rubbish someone had put on the curb. It was an old globe, imprinted with the names of nations that no longer existed: the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Czechoslovakia, The Free City of Danzig, Inini, French Somaliland, Hatay, Persia, The Empire of Japan, Nejd and Hejaz, Portuguese East Africa, Siam, Tibet, Bechuanaland, British Honduras and British Guiana, the Belgian Congo, Italian Cyrenaica, The Gold Coast, and Nyasaland. If whole countries had vanished and others were created, what did the fate of one piano-playing free thinker matter? Babies were good. Love and music were better.

She brought that globe home and stuck it on the mantle.

And then Emma began to live her life. Husbands and lovers, some better than others, all hungry, each in his own way, for something she couldn’t give them. Emma learned something from each one. She looked at the old globe whenever she felt her spirits flagging. For her, that globe was her ticket to another world. Like her music, seeing that globe, holding it and turning it on its stand helped her exist on another plane, above this earth, which, like countries, is transitory, while the music of the universe itself, the creation of matter and heaven bodies, of stars and of planets, and then their disappearance, the ebb and flow of being, was the rhythm and melody, the harmony Emma felt in her soul, and all that mattered to her. Love matters, Emma thought. Not the slings and arrows of the material world.

That was when she began to collect the things that inspired her to dream. The Christmas reindeer. The cans of salmon for the poor. The boxes of brownie mix so she could bake brownies for the librarians and the school secretaries. Plates with floral patterns and old silverware that was too precious to be destroyed — just think of the families who had used these plates and these forks and knives for their dinners going back a hundred years. The coats and sweaters for people who might be cold. She loved to imagine a whole herd of Christmas reindeer on her front lawn, lit up as soon as darkness fell, their heads moving together, left to right, right to left, and left to right again, so that people in their cars or people walking down the street might believe those reindeer were following them with their eyes, as those people moved in front of them. She loved to dream about the people in China who assembled those reindeer in factories, crammed into assembly lines, working twelve-hour shifts. Those people might well be Confucianists or Buddhist who honored their ancestors and might know nothing of the myths from the Alpine north, of jolly white men with beards who rose sleighs through the sky, and less about churches, snow, and sleighbells jingling. What did Chinese factory workers think about the crazy Americans who bought these reindeer? Did they think we worship the reindeer as gods?

Everything comes from someplace. Every speck of dust has meaning. God doesn’t play dice with the universe.

–

First, Vera rented a dumpster and had it dropped in the driveway. The she began to clear paths through the rubble. She put ten bins on the porch and filled them with what she found: more cans of cranberry sauce and canned salmon than she could count, a hundred boxes of brownie mix, ten unopened boxes that held light-up Christmas reindeer with heads that moved back and forth, piles of coats, sweaters and blankets, boxes of old china and boxes of tarnished silverware, the knives and forks now grey and rusted where the silverplate had worn off. And toys: Beanie Babies and gnomes with pink hair, toy cars and trucks made of bright green, white, red, and blue plastic. Vera made a bin for blankets, a bin for old plates and silverware, a bin for coats and sweaters, a bin for canned food, one for computer parts and cables and one for books and one for toys. I’ll take obvious trash to the dumpster, she thought, and have this place in ship-shape in no time. So, there will be room for the hospital bed in the old dining room. So, Emma will have a kitchen, a bathroom, and a bed on one floor and her piano, which Vera found under a pile of old newspapers and magazines, right there with her.

Vera wondered about how her aunt would react, of course. But that didn’t stop her. It wasn’t possible for anyone to live in that house with all the junk. And life was better than death. So, like it or not, Emma would have to adapt.

Vera called the fire department. They came on Saturday and built a wheelchair ramp over the front steps. They were volunteers, and wouldn’t accept any money for their work, but were grateful when Vera made them coffee and brownies, which she made form one of the boxes of brownie mix.

–

Emma came home the following Tuesday. It was November: the sun was bright but low in the sky, the leaves were gone from the trees, and the horizon was visible now through the trees and houses, so you could see the sun as it was setting too early in the afternoon, its glinting yellow light strong until it dipped below the horizon and made the sky in the southwest and southeast pink and blue as the light disappeared. You could hear the foghorns and ringing buoys from the harbor. The air smelled faintly of heating oil and of salt and seaweed from the shore, from the rocks and tiny beaches.

They brought Emma home in a transport ambulance van – white with red markings and a revolving dome light over the cab — with two attendants dressed in white uniforms and wearing heavy blue jackets against the cold. An ambulance only barely. They had Emma parked on a wheelchair that they locked in place in the back. There was a ramp for the wheelchair that slid out from under the back of the ambulance and then angled to the ground. One of the attendants wheeled the wheelchair down the ramp, tilting it backward and going very slowly so Emma didn’t roll away. Emma wore a blue leisure suit and had a pink and white blanket thrown around her shoulders.

“My word,” Emma said, when they wheeled her onto the porch and into the front parlor, which was visible for the first time in thirty years.

“It was necessary,” Vera said. “Because of the hospital bed.”

“I see,” Emma said. “My things?’

“Mostly recycled,” Vera said. “I gave away what I could. To feed the hungry and clothe the homeless. That sort of thing. Everything else went into the dumpster. The trash company is coming to pick it up tomorrow.”

“Anything left at all?” Emma said.

“Only what is absolutely necessary,” Vera said. “A couch. A few chairs, the ones that weren’t broken. Your piano, which I found under piles of newspapers. A microwave, a toaster, and a coffeemaker.”

“Those were my grandmother’s dishes…and an old globe I was particularly fond of,” Emma said.

“Clutter is dirt. Clutter is death. Do you want to know about the mouse nests and droppings I found? The snakeskins ands the rat skeletons?” Vera said.

All gone.

Everything that made Emma who she was had disappeared.

–

The earth suddenly cracked in two, cracked open like an egg, and great red and black flares roared out of the middle, as the earth’s molten core spewed out, as molten lava that was on fire, as bright as a solar flare, lashing into space and falling back to earth like whips, beating the planet into submission, punishing humans and animals alike for our many transgressions. Oh, feckless humanity. Unable to live. Unable to dream. Unable to be. The oceans evaporated into a giant cloud of stream, so the space where the earth had been was now just a ball of molten flame and white cloud. Vera, of course, was gone. She had been covered by molten lava. Where Vera had turned into a statue that looked like Vera but was stone, still smoking as it cooled, one hand raised, so it looked a little like the statute of Lady Justice, blindfolded, one hand raised, the other holding a sword. Lot’s unnamed, lost wife! Turned to stone, not salt, but still stuck blind and dumb for looking back, for yearning to be part of two worlds, punishment for feeling the love of her old life, now revealed to be corrupt, punishment for feeling that love in her soul as she was being marched off into a cleaned and well-ordered future, without dust or clutter.

–

“Emma?” Vera said. “It must feel strange to be here with the house looking like this.”

“Everything is different,” Emma said. “Neither better or worse or worst. Just different.”

“I think you will grow to like it,” Vera said. “I hope so. And hope you will forgive me. For doing what needed to be done.”

“Forgive you?” Emma said. “There’s nothing to forgive. I love you. You are my rock. My redeemer.”

“Bring my walker please,” Emma said to the ambulance attendants. “And lock the chair.”

“I learned something, you know,” Emma said, as one of the ambulance people brought her walker and set it in front of her, and the other kneeled to lock the wheels of the wheelchair, one wheel after the next. “In three months of rehab.”

Emma pulled herself up, pushing with her legs, one stronger than the other, as she pushed with her good arm and steadied herself with her weak arm. Standing, she walked with her walker to the piano, sat on the piano bench, and scooched around so she sat at the keyboard, her feet on the petals, her weak arm shaky but poised above the keys.

Then she began to play.

All of Michael Fine’s stories and books are available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking here. Join us!

___

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.